Migration – a prerequisite for the emergence of a metropolis

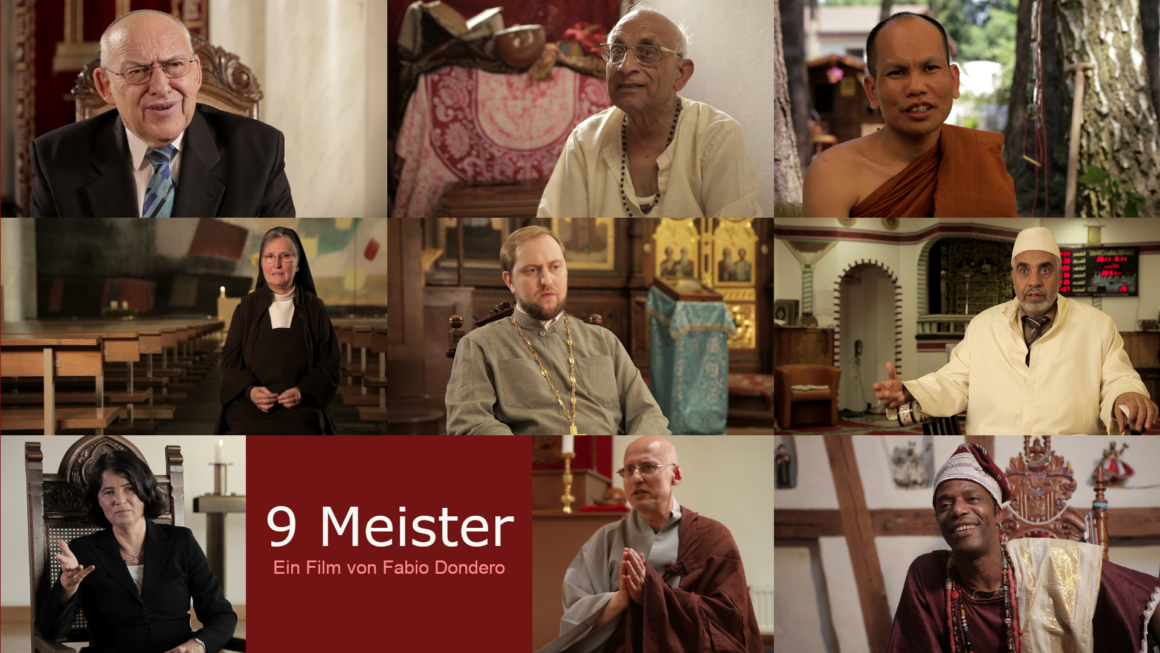

Berlin is mentioned for the first time in a document dated 1244. The settlement on the Spree and Havel develops into a city until the second half of the 16th century, under the rule of Frederick William of Brandenburg. The Great Elector of the Hohenzollern house operates a pragmatic and resolute reformist government policy and promotes immigration and religious tolerance: Bohemians, Polish, Dutch, displaced Jews from Austria, Huguenots from France, Protestants from Salzburg all find in the poor Brandenburg a new home. In Berlin the population of around 6,000 in 1650 rises to 57,000 in 1709. These are the early days of the Prussian kingdom.

In 1871 Berlin becomes the capital of the German Empire. Founder era, industrialization, more than four decades of perpetual peace (which ends in August 1914 with the beginning of World War I) let Germany rise to a world power and Berlin to a cosmopolitan city with a population explosion: in 1877 the metropolis counts one million inhabitants, 1900 almost two. Of these 2 million only 40% are born in the city, the others coming mainly from Brandenburg, East and West Prussia, Silesia, Pomerania, Posen and Saxony. The proportion of foreigners is 17% (in 2013 it was 14%).

From the Far East, from Russia, Galicia and Romania, Jews come to Berlin fleeing the pogroms under the Czars, from 1917 increasingly opponents and victims of the October Revolution. In 1918, after losing the war and the declaration of the Republic, Berlin has 3.9 million inhabitants, after 1925 more than 4. The Weimar Republic and the roaring Twenties are years of political, social and economic instability, as well as a flourishing time for art, science and culture.

In 1933 begins the darkest chapter of the city: Hitler is appointed chancellor. The totalitarian, racist and anti-Semitic policy of the Nazis transforms Germany into a dictatorship of violence and terror. People are being systematically attacked, persecuted and murdered because of their religious, political or sexual affiliation. The Jewish community of Berlin, with its 160,000 members, is annihilated. From 1939, with the outbreak of the war, the city is filled more and more with conscripted foreigners who soon account for 30% of the working population.

Expansion, delusion and militarization catapult the country and Europe to barbarism and a six-year World War II with an estimated 60 million deaths. The bitter urban warfare in Berlin is only the last tragic act of the conflict. Between 1944 and 1945, the city loses 1.6 million of its inhabitants and 30% of its buildings. On May 8, in a „Götterdämmerung“, the Nazis surrender unconditionally: Germania, the dream of the Third Reich, is over. What remains is unrecognizable, the traces of diversity are gone, the city, a gigantic ruin. Apart from the military forces of the occupying powers, the amount of foreigners of the population is now less than one percent. At no time since the Edict of Tolerance in 1685 so few members of religious and ethnic minorities live in Berlin. That will not change significantly until the early sixties.

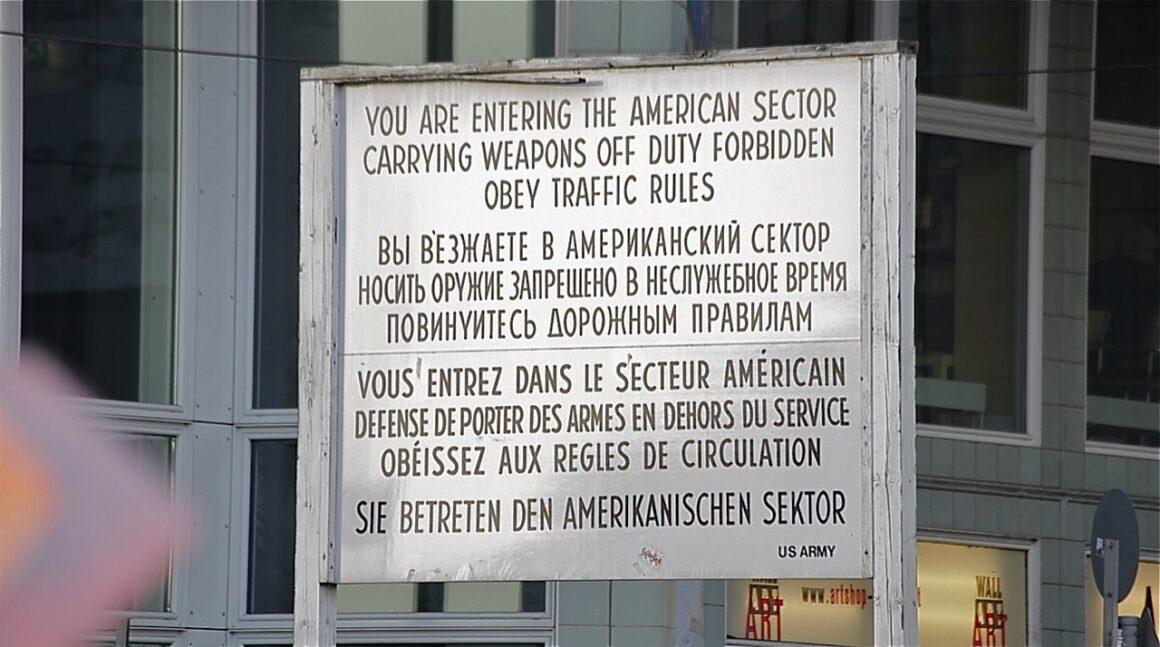

After the war, the city is divided into four sectors, administered by the British, French, Russians and Americans. The growing political differences among the victorious powers introduce to a new war period, this time cold. In 1949 two different states arise on German soil, the FRG and the GDR, and in 1961, a wall. Capitalists and Communists, armed with nuclear weapons, now threaten in a trembling stalemate a mutual and final destruction. This condition shapes the inhabitants‘ lives in a city that is located in the epicenter of the tensions of the world powers. West Berlin, highly subsidized, survives and evolves into a symbolic and somehow run-down island of freedom. In the eastern part of the city there is the dictatorship of the proletariat and a party controlled by Moscow, which discriminates against all dissidents with the help of an efficient as brutal state security service. For Marx, religion is the opium of the people.

The city suffers from the division, the east-west commuters being blocked paralyses West Berlin’s economy in 1961, which lacks labor force in the years of the economic miracle. Industry and politics seek to attract people from West Germany, offering allowances and exemption from army duty, but fails due to insufficient numbers. Eventually from 1964 (in West Germany the development rush has started in 1955 already) hundreds of thousands of migrant workers move to West Berlin. They come from Turkey, the former Yugoslavia, Greece, Spain and Italy. Some return home quickly, others remain forever. Between the late Seventies and the mid-Nineties tens of thousands of refugees follow from the crisis regions of Lebanon, Africa and the Balkans. In East Berlin, the development is very different: in addition to members of the Russian armed forces and political personnel, only sporadically Czechs, Poles and Hungarians are living and working in the city.

The peaceful revolution in 1989 marks the end of the SED dictatorship and of the GDR. In communities and churches DDR pacifists and opponents find public space for their demands for change. Vigils are held and attended by a growing number of people. The dusty nomenklatura party reacts irritated and with the use of force, but ultimately it is completely unprepared for the rapid international, political and financial unfolding of events, and is thus overrun in a few months by the anger and discontent of its own people. On the evening of November 9, 1989, the border at Bornholmer Strasse, between the divided districts Wedding / Prenzlauer Berg, after 28 years reopens.

On October 3 1990 the Unification Treaty between the FRG and the GDR is signed. This legally states the dissolution of the GDR state, its joining to the FRG and the reunification of Germany. Berlin, again capital of a united Germany, experiences a renaissance from now on. Every corner of the city is built and renovated, and from all over the world mostly young actors flock into the city.

In 2015 nearly 3,500,000 people from 190 countries are living in Berlin.

Turks: ~ 180,000-210,000, Polish: ~ 100,000 Russians: ~ 50,000 Palestinians: ~ 30,000, Serbs: ~ 26,000, Lebanese: ~ 25,000, Italians: ~ 22,000, Vietnamese: ~ 21,000, Americans: ~ 20,000, French : ~ 20,000, Kazakhs: ~ 20,000, Bulgarians: ~ 16,000, Ukrainians: ~ 16,000, British: ~ 15,000, Bosnians: ~ 14,000, Greeks: ~ 13,000, Austrians: ~ 13,000, Spaniards: ~ 13,000, Croats: ~ 12,000, Chinese : ~ 12,000, Iranians: ~ 11,000, Thais: ~ 11,000, Syrians: ~ 11,000, Romanians: ~ 11,000, Egyptians: ~ 10,000, Ghanaians: ~ 10,000, Israelis: ~ 10,000, Brazilians: ~ 10,000, Indians: ~ 10,000, Koreans : ~ 10,000.

Links:

Stadt der Vielfalt – Das Entstehen des neuen Berlin durch Migration, Sanem Kleff, Eberhard Seidel, Der Beauftragte des Senats von Berlin für Migration und Integration, Berlin 2009

Das Statistische Jahrbuch Berlin Brandenburg 2013

Wikipedia: Berlin